Distracted driving has been around longer than you think

Early examples of distracted driving studies go back as far as 1963, when scientist John Senders took to the roads blindfolded – all in the name of research.

The notion of distracted driving goes as far back as the invention of the automobile itself. There have always been external distractions–like billboards or people on the side of the road. Internal distractions are nothing new, either–tuning a radio, fiddling with the A.C., reaching for a French fry, or parenting from the front seat.

The pioneer of distracted driving

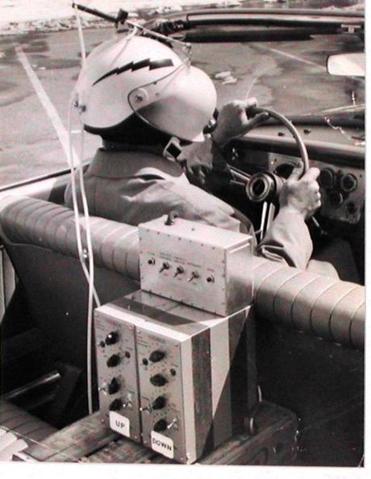

Early examples of distracted driving studies go back as far as 1963, when scientist John Senders took to the roads blindfolded--all in the name of research. The Bureau of Public Roads (now the Federal Highway Administration) tasked him with investigating how much time a driver had to spend looking at the roads to drive effectively. To gather his needed data, Senders hopped into a Dodge Polara and drove into midday traffic on I-495 in Massachusetts.

The twist: he was wearing a motorcycle helmet with a sandblasted opaque shield, which was rigged to a sensor that periodically flipped it down over his eyes. With the visor down, Senders could see nothing until he triggered it to lift again for a fraction of a second.

Senders’ findings were indicative of the future. He wrote in a report published in 1967 about the phenomenon of “road hypnotization": staring at the road ahead, but not actually seeing it. Senders noted a plethora of distractions tugging at drivers’ focus, including the rearview mirror, conversing with a passenger, and checking out landmarks.

This study led him to develop the “occluded vision paradigm as a measure of attentional demand” (now a part of the protocol for assessment of distraction). This technique is still used today in driving studies and has a long and diverse history of applications, including its use in the development of instrument panel designs in airplane cockpits.

Senders won an Ig Nobel Prize in Public Safety in 2011 for his study, “The Attentional Demand of Automobile Driving.” He died in 2019 at the age of 99.

The arrival of cell phones

If only Senders had known what was coming next.

In 1983, something arrived on the scene that drastically changed the definition of “distracted driving.” That year, cellular telephones were introduced to the American marketplace.

By 1997, the Cellular Telecommunications Industry Association (CTIA) reported that there were more than 50 million cellular customers in the U.S. That same year, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) launched one of the first intensive studies into the effects of wireless phones on driving.

Among those surveyed, nine out of 10 cellular telephone owners reported using them while driving. This study also surveyed the effects of driving and using a cellphone (inability to maintain speed, lane drifting, and weaving). The study highlighted comments by police officers, who were seeing an increased amount of odd behavior on the roads in conjunction with cell phone usage.

According to AT&T, today more than 90 percent of people say they know the dangers of texting and driving, yet many still find ways to rationalize their behavior.

Law enforcement takes action

Florida became the first state to ban the use of any sort of mobile communications device with a law against using headsets, headphones, or any other listening device in 1992. Arizona followed shortly after in 1996, with restrictions on the use of hand-held and/or hands-free communication devices by school drivers.

In 2001, several other states (New Jersey, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York) followed suit, enacting various bans on communications devices while driving. New York was the very first state to restrict the use of hand-held devices by all drivers.

Kentucky’s first law regarding distracted driving and cell phone usage was passed in 2007. It restricted the use of hand-held or hands-free devices by school bus drivers. On April 15, 2010, the Commonwealth House Bill 415 was signed into law, banning texting for drivers of all ages while a vehicle is in motion.

Today

In 2011, the number of wireless subscriber connections in the U.S. (315.9 million) surpassed the population (315.5 million), according to CTIA. Today, more than 97% of Americans own a mobile phone.

Currently, talking on a hand-held cellphone while driving is banned in 29 states, D.C., Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Thirty-six states and D.C. ban all cell phone use by novice or teen drivers, and 20 states and D.C. prohibit any cell phone use by school bus drivers.

Text messaging is banned for all drivers in 49 states (including Kentucky) and in D.C., Guam, and the Virgin Islands.

Click here to check out your state's laws regarding cellphone usage

In Kentucky, there is a texting ban. No laws currently restrict talking on a hand-held phone behind the wheel. Drivers younger than 18 and school bus drivers are under an “all cell phone ban,” which means these two groups are prohibited from any cell phone usage, including making hand-held phone calls.

The enforcement of these laws is “primary” in Kentucky, meaning a police officer may pull over and ticket a driver if he or she simply observes a violation in action.

In a society of increasingly unlimited availability, it’s obvious that this problem isn’t going away anytime soon. Don’t let a smiley face emoji be the reason you get a ticket–or worse. Please drive distraction-free.